Strategic Thinking Capability in Leadership Career Advancement

Elle Taurins, Faculty Lecturer, AIM Business School

Strategic thinking is consistently cited as one of the most critical leadership capabilities. While organisations consistently rank strategic thinking as the most valued leadership skill, only a minority of managers are seen as genuinely strategic. The situation raises questions about what the desired capability of “being strategic” really means, and why it is so difficult to develop. This article distils the insights from current academic research and practitioner perspectives to bridge theory and practice with the intent to start a discussion to assist organisations and senior leadership candidates seeking career advancement.

Why strategic thinking matters

Researcher findings correlate strategic thinking with organisational success (Salamzade et al., 2018) and competitive advantage (Liedtka, 1998). Its benefits include improved corporate decision-making, enhanced innovation, and more effective navigation of complexity (Goldman, 2006; Gross, 2017). Importantly, strategic thinking is not confined to CEOs or senior executives. Studies highlight its relevance across all organisational levels and sectors (APS, 2021; Young, 2016; Goldman, 2012). As global turbulence intensifies, leaders at all levels must cultivate the ability to anticipate change, reframe problems, and identify emerging opportunities.

The elusive concept of strategic thinking and practical challenges

The academic debate over what constitutes strategic thinking has endured for decades. Challenging questions whether strategic thinking can be taught and what the concept looks like in practice (Liedtka, 1998) continue to persist decades later. Academics offer a plethora of definitions, typically associated with visionary, creative, integrative thinking processes (Sahay, 2019), systems perspectives, and learning orientation (Casey & Goldman, 2010; Timuroglu et al., 2016). Specific conceptual models are proposed to illustrate strategic thinking (Bonn, 2005; Pisapia et al., 2005) but phenomenon remains vague. New managers and business graduates often conflate strategic thinking with strategic planning or strategic management (Mainardes et al., 201; Graetz, 2002).

In the public domain, a proliferation of strategy-related construct is overwhelming (221,000,000 Google results). Job platforms such as Indeed offers simplistic definitions of strategic thinking, equating it with breaking down tasks or problem solving. So, how do organisations and HR professionals articulate strategic thinking to the candidates for leadership positions?

From a recruitment perspective, employers struggle to evaluate strategic thinking capability reliably. Some assess candidates on three “disciplines” of acumen, allocation, and action (Horwath, (2020). Consultants propose structured interviews, simulations, or problem-solving tasks and promote using tools such as SWOT, scenario planning, or the balanced scorecard as proxies for strategic thinking (Allio, 2006). Executive coaches encourage job candidates to be noticed for transcending their job function (Bowman, 2023). However, these approaches often test analytical or planning skills rather than genuine strategic cognition. Emerging technologies, such as AI-powered analytics, promise to support strategic insight generation, yet even advocates admit that leaders remain essential in framing the right questions and interpreting insights (Watkins, 2023); AI can only generate operational-level strategies (Barnea, 2020; Eriksson et al., 2020; Korzynski et al, 2023).

Are there theoretical frameworks that practitioners could use as a guidance? There are two key models dominating academic discourse.

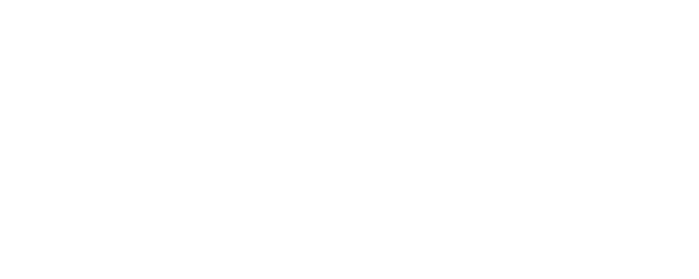

Liedtka’s (1998) multi-dimensional model (Figure 1) highlights strategic thinker’s ability to think creatively and critically simultaneously. It is underpinned by the systems thinking and converges the intent, hypothesising, opportunity spotting.

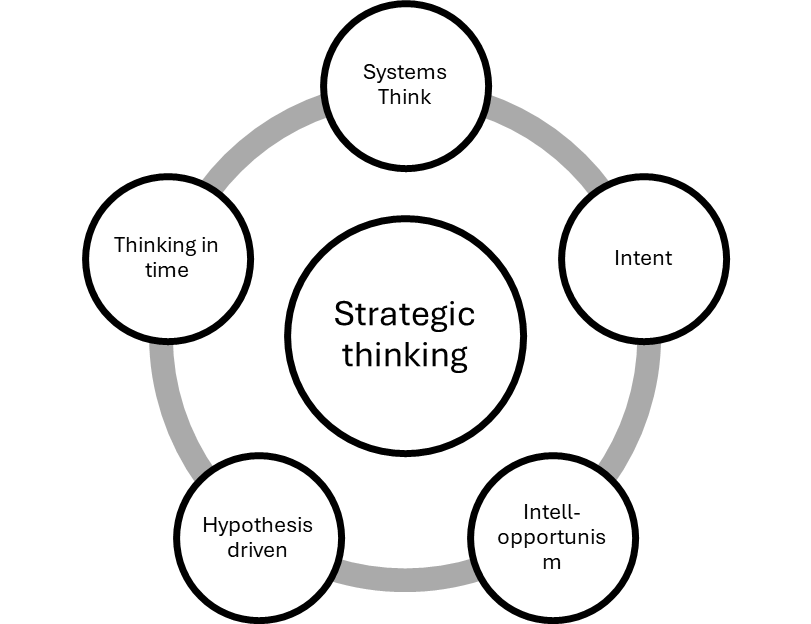

Bonn’s (2005) model (Figure 2) converges systems thinking, vision and creativity. This multi-layered model views strategic thinking as an integrative process in problem-solving, and highlights interconnectedness of internal and external environmental dynamics within the individual, group and organisational contexts.

Figure 1 Liedtka’s (1998) strategic thinking model

Figure 2 Bonn's strategic thinking model (2005)

Both models remain widely cited but are not systematically applied in leadership development programs. Attempts to adopt a theoretical framework to develop a practical model are scarce, with rare exceptions, like Australian Defence Force’s modified adaptation (Young, 2016). Considering the academic-practice gap, what could be other pathways to apply strategic thinking?

Leadership behaviours that foster strategic thought

Rather than focusing on abstract models, some researchers shifted the focus on leadership practices of strategic thinkers. Goldman (2012), identified 18 leadership practices, including scanning the external environment, rewarding strategic behaviours, and explicitly linking promotions to strategic thinking. The latter is intriguing, because justification of promotions would require an objective measurement of strategic thinking by HR professionals. So, how strategic thinking can be measured to be assessed?

A comprehensive US study (Goldman et al., 2015) of corporations employing over two million people showed that the assessment of strategic thinking ability was based on the supervisor’s assessment, and that some tools used, like 360-degree feedback, were not measuring strategic thinking at all. Although one of the most rigourous intruments such as Pisapia’s Strategic Thinking Questionnaire (STQ) (Pisapia et al., 2011) and subsequent refinements (Rodrigues et al., 2021) have been validated in research, there is little evidence of their adoption in practice. This gap in adoption of measuring tools undermines efforts to develop leaders with strategic mindset. Without clear metrics, managers struggle to benchmark their growth or verify strategic thinking capability. The next question then is How else can strategic thinking capability development can be facilitated?

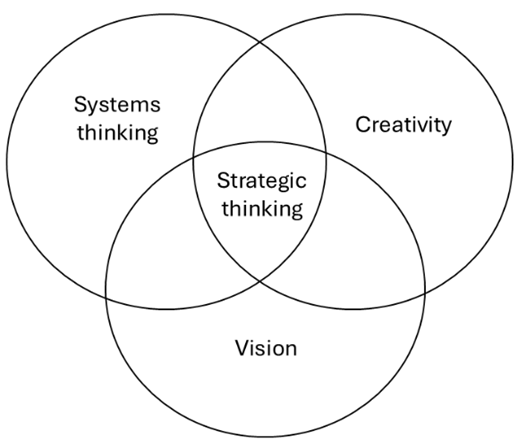

Goldman (2012) identified three key reasons for the gap in strategic thinking: a lack of understanding of the concept itself, confusion of the term among practitioners and scholars, and limited development of strategic thinking in leaders. The challenge is to design the method of developing a strategic thinking capability can be approached from the learning orientation perspective. The learning and strategic thinking interdependency is supported by research (Timuroglu et al., 2016). Drawing on Liedtka’s (1998) view of a strategic thinker as a learner, not a knower, strategic thinking is an outcome of a developmental process. Hence, leadership practices can be sequenced into the process of learning (Goldman, 2012). Casey and Goldman (2010) identified nine categories of work experiences fostering strategic thinking and proposed a non-linear model of Strategic Thinking in Action (Figure 3), which aligns with Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning and the emerging strategy theory (Mintzberg & Waters, 1985). From the reviewed frameworks, this model looks most promising for adoption in the organisational context due to its structure. Its components can be potentially deconstructed into skill sets, which, upon the development of some proficiency by the learners, may later inform strategic thinking knowledge and capability formation. So far, unorthodox management training methods like game theory simulations (Benito-Ostolaza & Sanchis-Llopis, 2014) show potential in developing planning skills rather than strategic mindset.

Figure 3. Strategic Thinking in Action (Casey & Goldman, 2010)

While there are avenues for further research or tools testing, they would take time to produce tangible results. Meanwhile, organisations, recruiters and leadership candidates need practical guidance on how to navigate the situation. Hence, the final question: What are short-term practical suggestions to practitioners, recruiters and educators?

Practical implications

Considering the abstract nature of the strategic thinking concept, the effort should be in building mutual understanding among the engaged parties of their expectations, so that these could be adequately addressed. Below are some suggestions to ignite a discussion:

- For recruiters and HR professionals to provide more specific guidance and interpretation of the level of strategic thinking expected (such as corporate or functional) and which aspects of strategic thinking candidates should demonstrate.

- For organisations to consider the validity of the tools currently used to assess strategic thinking, and adopt new validated assessment tools to reduce individual biases.

- For candidates to be more interview-savvy by probing specific aspects of the recruiter’s expectations about their strategic thinking proficiency, rather than guessing the meaning of ‘being strategic’.

- For executive educators to take a more focused approach to differentiate strategic concepts and demonstrate practical outcomes supported by applied research.

In conclusion, this overview of theoretical foundations and professional practices exposed a gap in practice between academics and practitioners. Research showed a positive correlation between higher executive education and strategic thinking development, and educators and practitioners should initiate a robust dialogue and collaboration, because without bridging the gap, the desired strategic leadership potential will remain hidden.

References

Allio, R. J. (2006). Strategic thinking: The ten big ideas. Strategy & Leadership, 34(4), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570610676837

APS (2021, August 21). Australian Public Service Integrated Leadership System (ILS), https://www.apsc.gov.au/working-aps/aps-employees-and-managers/classifications/integrated-leadership-system-ils/ils-resources-profiles-comparatives-and-self-assessment/integrated-leadership-system-ils-aps-1-6-comparative

Barnea, A. (2020). How will AI change intelligence and decision-making? Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 10(1), pp. 75-80.

Benito-Ostolaza, J.M., & Sanchis-Llopis, J.A. (2014). Training strategic thinking: Experimental evidence. Journal of Business Research, 67, 785-789.

Bonn, I. (2005). Improving strategic thinking: A multilevel approach. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(5), 336-354. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510607844

Bowman, N. A. (2023). Four ways to improve your strategic thinking skills. Harvard Business Review, 18–19.

Casey, A. J., & Goldman, E. F. (2010). Enhancing the ability to think strategically: A learning model. Management Learning, 41(2), 167-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507609355497

Eriksson, T., Bigi, A., & Bonera, M. (2020). Think with me, or think for me? On the future role of artificial intelligence in marketing strategy formulation. The TQM Journal, 32(4), 795-814.

Goldman, E. F. (2006). Strategic thinking at the top: What matters in developing expertise. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2006.22898564

Goldman, E. F. (2012). Leadership practices that encourage strategic thinking. Journal of Strategy and Management, 5(1), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554251211200437

Goldman, E. F., Scott, A. R., Follman, J. M (2015). Organizational practices to develop strategic thinking. Journal of Strategy and Management, 8(2), 155-175. DOI 10.1108/JSMA-01-2015-0003.

Graetz, F. (2002). Strategic thinking versus strategic planning: Towards understanding the complementarities. Management Decision, 40(5), 456-462. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740210430434

Gross, R. (2017). Exploring the moderating impact of absorptive capacity on strategic thinking, innovative behavior, and entrepreneurial orientation at the organizational level of analysis. Journal of Management Policy & Practice, 18(3), 60–73.

Horwath, R. (2020). The 3 Disciplines of strategic thinking. Personal Excellence, 25(3), 26–27.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, Prentice Hall.

Korzynski, P., Mazurek, G., Altmann, A., Ejdys, J., Kazlauskaite, R., Paliszkiewiwicz, J., Wach, K., & Zmieba, E. (2023). Generative artificial intelligence as a new context for management theories: analysis of ChatGTP. Central European Management Journal, 31(1), 3-13.

Liedtka, J. M. (1998). Strategic thinking: Can it be taught? Long Range Planning, 31(1), 120-129.

Mainardes, E. W., Ferreira, J. J., & Raposo, M. L. (2014). Strategy and strategic management concepts: Are they recognised by management students? E+M Ekonomie a Management, 17(1), 43-61. DOI:10.15240/tul/001/2014-1-004

Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning, The Free Press.

Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J.A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257-272.

Pisapia, J., Morris, J. D., Cavanaugh, C., & Ellington, L. (2011). The strategic thinking questionnaire: Validation and confirmation of constructs. The 31st SMS Annual International Conference, Miami, Florida, November 6-9, 2011.

Pisapia, J., Reyes-Guerra, D. & Coukos-Semmel, E. (2005). Developing the leader’s strategic mindset: Establishing the measures. Leadership Review, 5, 41-68.

Rodrigues, R.I., Ferreira, A., & Neve, J. (2021). Strategic thinking: The construction and validation of an instrument. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 52(3), 241–250. DOI:10.24425/ppb.2021.137888

Sahay, A. (2019). Strategic thinking: My encounter. 3D: IBA Journal of Management & Leadership, 10(2), 7–14.

Salamzadeh, Y., Bidaki, V. Z., & Vahidi, T. (2018). Strategic thinking and organizational success: Perceptions from management graduates and students. Global Business & Management Research, 10(4), 1–19.

Timuroglu, M. K., Naktiyok, A., & Kula, M. E. (2016). Strategic thought and learning orientation. South Asian Journal of Management, 23(4), 7–30.

Watkins, M. D. (2023). How AI will transform strategic thinking in business. I by IMD, 9, 36–37.

Young, M. L. (2015). Developing Strategic Thinking. Australian Army Journal, 13(2), 5-22.